London, United Kingdom, June 2021 – The Centre for the Protection of National Infrastructure (CPNI), which is the UK Government’s technical authority for physical and personal security, has launched a new study on the prevention of vehicle borne threats and Vehicle Borne Improvised Explosive Device (VBIED). In this PACTESUR guide, a CPNI representative* explores the ways in which vehicle as a weapon (VAW) attacks manifest themselves, including the environments they occur in, the response of people, security operations and emergency services.

Vehicles have been used for decades to facilitate terrorist attacks, traditionally the most recognised form being a Vehicle Borne Improvised Explosive Device (VBIED), in other words a vehicle full of explosives. Vehicles have also been used in countless attacks to facilitate armed assaults on sites and people, either using the vehicle to ram through protective security measures or simply transporting attackers and their materiel.

As with all threats, their nature and frequency fluctuate, and the attack methodologies evolve. In recent years Vehicle As a Weapon (VAW) has been the most prominent vehicle borne threat, however VAW attacks are not new.

In order to complement their longstanding countermeasure development programme and develop contemporary risk-based security advice, CPNI have reviewed over 150 VAW attacks and analysed many to develop a detailed understanding of how they manifest themselves.

Peaking in 2017, CPNI assesses there have been over 140 VAW attacks since 2014, predominantly in Europe, North America and Western Asia, the majority of those occurring in publicly accessible locations. Approximately 50% have occurred in Israel and the West Bank/Gaza and 20% in Europe.

European and North American countries have seen VAW attacks consistently used by individuals motivated by different ideologies or reasons.

The vast majority of the attacks can be attributed to extreme Islamist terrorists, a significant number to extreme right wing terrorists. The remainder had other grievances or disgruntlement, or their motives were less clear due to the presence of mental ill-health or intoxication.

- VAW attacks frequently begin on public roads with little or no warning, targeting crowded locations or where the opportunity to attack a specific demographic of people is present. The iconic nature of an event, an area or location can also influence the attacker.

- VAW attacks are of low complexity, require little planning, are quite often spontaneous and are frequently the first part of a Layered Attack; followed by a marauding attack, typically using bladed weapons and occasionally firearms. Most attacks occur using legitimately acquired cars, sports utility vehicles or vans. Injury and fatality rates vary significantly depending on the vehicle type and its speed, the crowd density, orientation and posture, their situational awareness and response and the response of the emergency services.

- Attackers generally do not follow the rules of the road, but they may not drive in a manner that risks ending the attack prematurely, rendering the vehicle unusable or seriously injuring themselves.

- Consequently, the attacker may tend to avoid obstacles, including relatively insubstantial ones.

The issues and opportunities

Justifying counter-terrorism protection of Publically Accessible Locations (PALs) is challenging in terms of prioritising where to protect, to fund and adapt to engineering constraints whilst meeting the architectural and business/operational needs of the area.

PALs are not isolated single use sites, more often they are mixed economies, a blend to some degree or other of hospitality, entertainment, social, shopping, business, residential, public and people transit spaces.

A terrorist attacker will often pay no regard to property boundaries and will exploit any opportunity or weaknesses that facilitates their objective, including using multiple attack methodologies. As such, layered security and collaboration with key stakeholders is essential to effective mitigation.

In short, when considering the risks and potential mitigation options, consider the area to be protected, its surroundings and the use of space, in essence recognising the opportunities for, and the needs of the local enterprises. The opportunities for public / private partnership are great and the benefits are often mutually symbiotic.

For Local Authorities and businesses, robust governance structures, access to detailed threat information and security advice is a prerequisite in order that the senior risk owners (Chief Executives / Elected members) can make informed decisions. Following structured risk management processes helps identify the challenges, opportunities, and risks, and will help develop cohesive and reasonably practicable mitigation strategies.

Close collaboration with counter-terrorism security specialists will help inform threat, planning assumptions and where appropriate help develop risk-based options, designs and implementation of operational and physical protective security measures to Deter, Detect, Delay, Mitigate and Respond to incidents and attacks.

And naturally, deployment of counter-terrorism security measures should be a supplement to Designing out Crime and Crime Prevention through Environmental Design practices. In the UK, essential to this are the Police counter-terrorism security advisor cadre, the Designing out Crime officers and local resilience fora.

At a strategic level, best practice would address these six priorities:

- Development of protective security risk frameworks to assist local authorities prioritise places to protect and manage residual risks. Risk owners should be considering:

- Threats and attack methodologies;

- Potential impact of an attack;

- Vulnerabilities

- Characterising the risks;

- Protective security strategies and risk-based options;

- Organisational readiness;

- Implementing reasonably practical security processes, measures, and response plans.

- Providing counter-terrorism protective security guidance, training and advice to businesses, local authorities and the emergency services.

- Cross Government collaboration (at local and national levels).

- Collaborate with, and professionalise, reputable security consultancies and security guarding professionals.

- Collaborate and, where appropriate, unify emergency response practices.

- Be prepared to adapt as the threats will continue to evolve and potentially surge.

Vehicle Borne Threats – Physical Mitigation

Understanding how VAW attacks manifest themselves, including the environments they occur in, the response of people, security operations and emergency services provides opportunities to apply risk based VAW mitigation strategies that encompass ‘layered’ security.

The proven method of stopping a hostile vehicle is through the deployment of Vehicle Security Barriers (VSB), those that have undergone vehicle impact testing in accordance with internationally recognised standards and received a performance rating. These barriers provide the highest level of assurance that the people or assets will be protected against vehicle borne threats.

There are well over 500 rated VSBs available. 470 are listed in CPNI’s Catalogue of Security Equipment that can stop a range of threat vehicles at different speeds and impact angles.

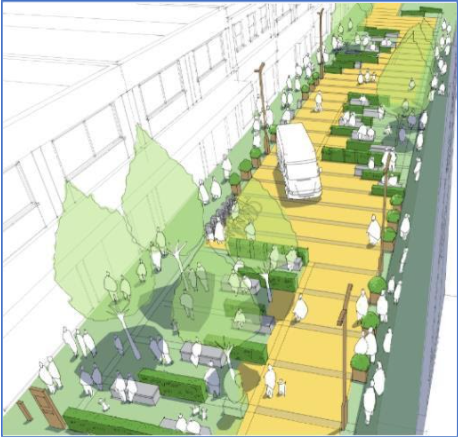

VSBs come in many shapes and sizes; overt and robust in appearance, blended and visually pleasing, dual use such as seating, information signs and other street furniture, landscape such as bunds and berms and temporary barriers.

Manufacturers of vehicle security barriers and street furniture have also invested heavily in making the products adaptable for the urban realm, creating barriers that have very shallow foundations and or no fixtures, thus saving considerable sums in civil costs and avoiding moving services.

In the built environment, counter-terrorism security measures need not be expensive, overt or oppressive. Done well, they can complement the architecture, help build a sense of space, assure the public and indirectly present additional business, social, environmental and economic opportunities. But it’s not just about the products available, how you deploy the VSBs is as important as the level of protection they provide. Clearly, VSBs should be installed in the same configuration in which they received their rating, but beyond that there are a multitude of protective security schemes that urban designers and security risk owners should consider, including:

- Total traffic exclusion (No vehicles allowed)

- Controlled vehicle inclusion (Some vehicles allowed)

- Footway protection (Pedestrian protection on the footway)

- Traffic calming to enforce slower vehicle speeds

- Semi-permanent protection (Permanently installed gates or socketed barriers occasionally closed)

- Temporary protection (Short-term deployment of portable barriers)

- Do nothing (no protection)

Physical interventions can all be enhanced by personnel security measures

An individual or group may identify a PAL as a potential target, and in doing so they will want to obtain current, reliable and credible information by conducting hostile reconnaissance to inform their attack planning. Ensuring organisations have security minded communications strategies is essential to this, it will ensure the right security messages are placed in the public domain and also ensure sensitive information is not released.

Authorities and businesses employ a very broad range of staff and contractors, many of whom will know and spend much time in PALs. They are a security asset so ensuring they are vigilant and responsive to, for example, suspicious or aggressive activity, abandoned bags or attempts at concealing devices or weapons in bins, planters or hidden in or behind other street furniture etc.

The posture and professionalism of security staff is critical in the perception a hostile will build of a PAL, and play a role in deterring hostile reconnaissance and an attack.

Hostile Vehicle Mitigation (HVM) is a term the UK applied to this specialism 3 decades ago. It is not just about deploying impact-rated products, it is a discipline, and one of its fundamentals is risk reduction. Knowing the threat, vulnerabilities and consequences of an attack will help duty owners assess, mitigate and/or accept the residual risk.

* The author has requested anonymity for security reasons. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of Efus.

About PACTESUR

The PACTESUR project aims to empower cities and local actors in the field of security of urban public spaces facing threats, such as terrorist attacks. Through a bottom-up approach, the project gathers local decision makers, security forces, urban security experts, urban planners, IT developers, trainers, front-line practitioners, designers and others in order to shape new European local policies to secure public spaces against terrorist attacks